Technical Resources

Educational Resources

APM Integrated Experience

Connect with Us

This section presents Java logging basics, including how to create logs, popular logging frameworks, how to create some of the best log layouts, and how to use appenders to send logs to various destinations, as well as advanced topics like thread context and markers.

Logging in Java requires using one or more logging frameworks. These frameworks provide the objects, methods, and configuration necessary to create and send log messages. Java provides a built-in framework in the java.util.logging package. There are also many third-party frameworks, including Log4j, Logback, and tinylog. You can also use an abstraction layer, such as SLF4J and Apache Commons Logging, which decouples your code from the underlying logging framework so you can switch between logging frameworks on the fly.

Choosing a logging solution depends on various factors, such as the available features, the complexity of your logging needs, ease of use, and personal choice. Another factor to consider is compatibility with other projects. For example, Apache Tomcat is hard-coded to use java.util.logging, although you can redirect logs to an alternative framework. You'll need to account for your environment and dependencies when choosing a framework.

For most developers, Log4j is a good choice as it provides solid performance, is extremely configurable, and has a highly active development community. If you plan on integrating other Java libraries or applications into your own, consider using SLF4J with the Log4j binding for the greatest compatibility.

Abstraction layers such as SLF4J decouple the underlying logging framework from your application, allowing you to change logging frameworks on demand. The abstraction layer provides a generic API and determines which logging framework to bind to at runtime based on the frameworks available on the application's classpath. If a framework isn't available on the classpath, the abstraction layer effectively disables log calls. Abstraction layers are useful when you plan on upgrading or switching frameworks down the road or if you're developing a library for use in other projects.

Java takes a customizable and extensible approach to logging. While Java provides a basic logging API through the java.util.logging package, you can use one or more alternative logging solutions instead. These solutions provide different methods for creating log data but share the same basic structure.

The Java logging API consists of three core components:

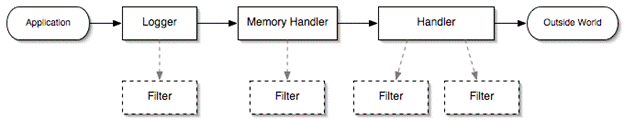

Loggers are responsible for capturing events (called LogRecords) and passing them to the appropriate Appender.Appenders (also called Handlers in some logging frameworks) are responsible for recording log events to a destination. Appenders use Layouts to format events before sending them to an output.Layouts (also called Formatters in some logging frameworks) are responsible for converting and formatting the data in a log event. Layouts determine how the data looks when it appears in a log entry.When your application makes a logging call, the Logger records the event in a LogRecord and forwards it to the appropriate Appender. The Appender then formats the record using a Layout before sending it to a destination such as the console, a file, or another application. Additionally, you can use one or more Filters to specify which Appenders should be used for which events. Filters aren't required, but they give you greater control over the flow of your log messages.

Source: https://docs.oracle.com/javase/7/docs/technotes/guides/logging/logging2.gif

The control flow used to log events in java.util.logging. © 2022 Oracle. All rights reserved.

In most cases, logging frameworks are configured through configuration files. These files are bundled with your application executable and are loaded by the logging framework at runtime. Although you can configure logging frameworks through code, using a configuration file is the preferred method as it consolidates all configuration settings in a single location. Most of the configuration examples provided in this guide use configuration files.

java.util.logging stores its configuration in a file called logging.properties. It uses the Properties format to store settings as key/value pairs. When Java is installed, it adds a global configuration file to the lib folder of the Java installation directory. However, you can specify your own configuration file by setting the java.util.logging.config.file property when running a Java program. This lets you create and store logging.properties files with individual projects.

The example below shows an Appender being defined in a global logging.properties file:

# Default file output is in the user's home directory.

java.util.logging.FileHandler.pattern = %h/java%u.log

java.util.logging.FileHandler.limit = 50000

java.util.logging.FileHandler.count = 1

java.util.logging.FileHandler.formatter = java.util.logging.XmlFormatter

Log4j supports multiple different configuration file formats, including XML, JSON, and YAML. When your Java application starts, Log4j searches for a log4j2.<format> file in the project directory. If it doesn't find one, it will default to console output. You can find configuration examples in the Log4jdocumentation.

Note this guide refers to Log4j 2, not Log4j 1.x. Log4j 1.x has been officially deprecated and should no longer be used.

Logback uses a logback.xml file, which has an XML syntax similar to Log4j. You can also provide a logback.groovy file, which uses the Groovy format instead of XML. You can find examples for each file type through their respective links.

Loggers are objects that trigger log events. Loggers are created and called in the code of your Java application, where they generate events before passing them to an Appender. A class can have multiple independent Loggers responding to different events, and you can nest Loggers under other Loggers to create a hierarchy.

The process of creating a new Logger is similar across logging frameworks, although the exact method names may be different. For example, in java.util.logging, you create a new Logger using Logger.getLogger(). getLogger() takes a string parameter identifying the name of a Logger. If a Logger with that name already exists, then that Logger is returned; otherwise, a new Logger is created. It's generally good practice to name a new Logger after the current class using class.getName():

Logger logger = Logger.getLogger(MyClass.class.getName());

Loggers provide several methods for triggering log events. However, before you can log an event, you need to assign a level. Log levels determine the severity of the log and can be used to filter the event or send it to a different Appender (for more information on log levels, see the Log Levels section). The Logger.log() method requires a level in addition to a message.

logger.log(Level.WARNING, "This is a warning!");

Most logging frameworks provide shorthand methods for logging at a particular level. For example, the following statement produces the same output as the previous statement:

logger.warning("This is a warning!");

You can also prevent a Logger from logging messages below a certain level. In this example, the Logger only logs events at or above a WARNING level, while all other events are dropped. Note that in some frameworks (such as Log4j2), this is a configuration setting.

logger.setLevel(Level.WARNING);

There are more methods available for recording additional information. For example, logp() (log precise) lets you specify the source class and method for each log entry, while logrb() (log with resource bundle) lets you specify a resource bundle to use for localization. entering() and exiting() lets you log method calls for tracing the execution flow of your program and so on.

Appenders forward logs from Loggers to an output destination. During this process, log messages are formatted using a Layout before being delivered to their final destination. Multiple Appenders can be combined to write log events to multiple destinations. For instance, a single event can be simultaneously displayed in a console and written to a file.

Note the java.util.logging refers to Appenders as Handlers.

Most logging frameworks provide similar Appenders but vary in how those Appenders are implemented. With java.util.logging, you can add an Appender to a Logger using the Logger.addHandler() method. For example, the following command adds a new ConsoleHandler, which outputs log events to the console:

logger.addHandler(new ConsoleHandler());

A more common approach is to add an Appender using the configuration file. With java.util.logging, Appenders are defined in a comma-separated list. This example adds both the console and a log file as destinations:

handlers=java.util.logging.ConsoleHandler, java.util.logging.FileHandler

For XML-based configuration files, Appenders are added as an element underneath the element. With Log4j, we can easily add a new ConsoleAppender for sending log messages to System.out.

<Console name="console" target="SYSTEM_OUT">

<PatternLayout pattern="%m%n" />

</Console>

This section describes some of the more common Appenders and how they're implemented in various logging frameworks.

One of the most common Appenders is the ConsoleAppender, which simply displays log entries in the console. The ConsoleAppender is used as the default Appender for many logging frameworks and comes preconfigured with basic settings. Each Appender can be configured using several parameters. For example, you can see the supported parameters for a ConsoleAppender in the Log4j appender documentation.

A complete Log4j2 configuration file may look like this:

xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<Configuration status="warn" name="MyApp">

<Appenders>

<Console name="MyAppender" target="SYSTEM_OUT">

<PatternLayout pattern="%m%n"/>

</Console>

</Appenders>

<Loggers>

<Root level="error">

<AppenderRef ref="MyAppender"/>

</Root>

</Loggers>

</Configuration>

This configuration creates a ConsoleAppender named MyAppender, which uses a PatternLayout to format the details of the event before writing it to System.out. The <Loggers> element provides configuration for the Loggers defined in your code. The only Logger used in this example is the Root Logger, which accepts all messages by default. However, since we set level="error", the Logger will only accept messages at or above an ERROR level. If we use logger.error() to record a message, it appears on the console like so:

An unexpected error occurred.

You can achieve the same output using Logback.

<configuration>

<appender name="MyAppender" class="ch.qos.Logback.core.ConsoleAppender">

<encoder>

<pattern>%m%n</pattern>

</encoder>

</appender>

<root level="error">

<appender-ref ref="MyAppender" />

</root>

</configuration>

FileAppenders write log entries to files. FileAppenders are responsible for opening and closing files, appending entries to files, and locking files to prevent data corruption or overwriting.

To create a FileAppender in Log4j, specify the name of the destination file, whether to append or overwrite, and whether to lock the file while recording entries.

...

<Appenders>

<File name="MyFileAppender" fileName="myLog.log" append="true" locking="true">

<PatternLayout pattern="%m%n"/>

</File>

</Appenders>

...

This creates a FileAppender named MyFileAppender, which writes events to myLog.log. The appender automatically locks the file while writing to it, preventing other processes from overwriting your data.

With Logback, you can ensure file integrity by enabling prudent mode. Prudent mode increases the cost of writing to files but safely manages file writes from multiple FileAppenders and also from multiple Java programs.

...

<appender name="FileAppender" class="ch.qos.Logback.core.FileAppender">

<file>myLog.log</file>

<append>true</append>

<prudent>true</prudent>

<encoder>

<pattern>%m%n</pattern>

</encoder>

</appender>

...

SyslogAppenders send log entries to a syslog server running on a local or remote system. Syslog is a service that runs on a device and collects logs from the device's OS, processes, and services. Logs collected by syslog can range from hardware events to user logins to diagnostic information. Syslog events are categorized by facility, which specifies the type of event being logged. For instance, the auth facility tells syslog that an event is related to security and authentication.

SyslogAppenders are natively supported in Log4j and Logback. To create a SyslogAppender in Log4j, specify the host number, port number, and protocol the syslog is listening on. The example below also specifies a facility:

...

<Appenders>

<Syslog name="SyslogAppender" host="localhost" port="514" protocol="UDP" facility="Auth" />

</Appenders>

...

You can do the same with Logback.

...

<appender name="SyslogAppender" class="ch.qos.Logback.classic.net.SyslogAppender">

<syslogHost>localhost</syslogHost>

<port>514</port>

<facility>Auth</facility>

</appender>

...

We've covered some of the more commonly used Appenders. There are dozens of additional Appenders that add new capabilities and build on other Appenders. For instance, the RollingFileAppender in Log4j extends FileAppender by automatically rolling over log files when a certain condition is met. The SMTPAppender sends an email containing the contents of the log. The FailoverAppender automatically switches to a different Appender in case one or more Appenders fail during the logging process. For more information on other Appenders, see the Log4j Appenders reference and the Logback Appenders reference.

Choosing which Appender to use depends on your logging requirements. For example, if you're developing an application and want to quickly debug an issue, a ConsoleAppender is one of the easiest ways to view your logs in real-time. If you're running an application in production, a FileAppender or SyslogAppender will let you recover older logs from a file.

If you're unsure whether a certain Appender will affect your application's performance, check out our benchmark comparison of Log4j, Logback, and SLF4J.

Layouts convert the contents of a log entry from one data type into another. Logging frameworks provide Layouts for plain text, HTML, Syslog, XML, JSON, serialized, and other logs.

Note that java.util.logging refers to Layouts as Formatters.

For example, java.util.logging provides two Layouts: the SimpleFormatter and the XMLFormatter. SimpleFormatter, the default Layout for ConsoleHandlers, outputs plain text log entries similar to this:

May 14, 2019 10:47:51 AM MyClass main

SEVERE: An exception occurred.

XMLFormatter, the default Layout for FileHandlers, outputs log entries similar to this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<!DOCTYPE log SYSTEM "logger.dtd">

<log>

<record>

<date>2019-05-19T10:47:51</date>

<millis>1557866904</millis>

<sequence>0</sequence>

<logger>MyClass</logger>

<level>SEVERE</level>

<class>MyClass</class>

<method>main</method>

<thread>1</thread>

<message>An exception occurred.</message>

</record>

</log>

XMLFormatter, the default Layout for FileHandlers, outputs log entries similar to this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<!DOCTYPE log SYSTEM "logger.dtd">

<log>

<record>

<date>2015-03-31T10:47:51</date>

<millis>1427903275893</millis>

<sequence>0</sequence>

<logger>MyClass</logger>

<level>SEVERE</level>

<class>MyClass</class>

<method>main</method>

<thread>1</thread>

<message>An exception occurred.</message>

</record>

</log>

Layouts are typically configured using a configuration file, although starting with Java 7, SimpleFormatters can be configured using a system property.

For example, one of the most common Layouts in Log4j and Logback is the PatternLayout.

PatternLayout lets you determine how data is extracted from log events and formatted for output based on a conversion pattern. Conversion patterns act as placeholders for data appearing in each log event. For example, let's break down a PatternLayout commonly used in Log4j:

<PatternLayout pattern="%d{HH:mm:ss.SSS} [%t] %-5level %logger{36} - %msg%n"/>

%d{HH:mm:ss.SSS} formats the date in terms of hours, minutes, seconds, and milliseconds.%t displays the Logger's current thread.%level displays the severity of the log event.%logger displays the name of the Logger.%m displays the event's message.%n adds a new line for the next event.Here are several examples of log events formatted using this conversion pattern:

16:42:14.271 [main] INFO main: initializing worker threads

16:42:15.990 [worker] DEBUG worker: listening on port 12222

16:42:20.010 [worker] INFO worker: received request from 192.168.1.200

16:42:20.100 [worker] ERROR worker: unknown request ID from 192.168.1.200

The PatternLayout class from Log4j and Logback supports conversion patterns, which determine how data is extracted from log events and formatted for output. A subset of those patterns is shown below. While these particular fields are the same in both Log4j and Logback, not all fields use the same patterns. To learn more about PatternLayouts, see the documentation for Log4j and Logback.

To use a different Layout with java.util.logging, set the Appender formatter property to the Layout of your choice. To do this in code, you can create a new Handler and use its setFormatter() method, then assign the Handler to the Logger using logger.AddHandler(). The following example creates a ConsoleHandler for formatting logs using an XMLFormatter instead of the default SimpleFormatter:

Handler ch = new ConsoleHandler();

ch.setFormatter(new XMLFormatter());

logger.addHandler(ch);

This causes the Logger to print the following output to the console:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<!DOCTYPE log SYSTEM "logger.dtd">

<log>

<record>

<date>2015-03-31T10:47:51</date>

<millis>1427813271000</millis>

<sequence>0</sequence>

<logger>MyClass</logger>

<level>SEVERE</level>

<class>MyClass</class>

<method>main</method>

<thread>1</thread>

<message>An exception occurred.</message>

</record>

</log>

For more information on Layouts in Log4j and Logback, see the Log4j Layouts reference and the Logback Layouts reference.

Custom Layouts let you specify how Appenders output log entries. While it's possible to tweak the SimpleFormatter output, the SimpleFormatter limits you to plain text messages. More advanced formats, such as HTML or JSON, require either a custom Layout or a separate framework. For more details on creating custom Layouts for java.util.logging, see the Formatters section of the Java Logging Overview.

Log levels provide a way to categorize logs by their severity or their impact on the overall health and stability of the application. java.util.logging provides the following levels, which are listed by decreasing severity:

java.util.logging also provides two additional levels: ALL and OFF. ALL causes the Logger to log all messages regardless of level, while OFF disables logging.

Setting a level causes a Logger to ignore messages below that level. For example, the following statement causes the Logger to ignore messages below the WARNING level:

logger.setLevel(Level.WARNING);

However, any messages having a level of WARNING or SEVERE will be logged by the Logger. This can also be set in the configuration file by changing the Logger's LoggerConfig:

...

<Loggers>

<Logger name="MyLogger" level="warning">

...

If you've ever experienced an exception in a Java program, chances are you've come across a stack trace. Stack traces provide a snapshot of the program's active method calls, allowing you to pinpoint your place in the program's execution.

For example, the following stack trace was generated after a program tried to open a file that didn't exist. In this example, the class FooClass uses a FileReader to try to read a file called foo.file from the main method. There is no foo.file in the application directory or classpath, causing the Java VM to throw a FileNotFoundException. Since we attempt the read within a try-catch block, we can catch the exception and prevent a crash. We can also use the opportunity to pass the exception to a logging framework, resulting in the following log:

[ERROR] main: Unable to open file! java.io.FileNotFoundException: foo.file (No such file or directory)

at java.io.FileInputStream.open(Native Method) ~[?:1.7.0_79]

at java.io.FileInputStream.(FileInputStream.java:146) ~[?:1.7.0_79]

at java.io.FileInputStream.(FileInputStream.java:101) ~[?:1.7.0_79]

at java.io.FileReader.(FileReader.java:58) ~[?:1.7.0_79]

at FooClass.main(FooClass.java:47)

The latest versions of Log4j and Logback automatically append %xEx (stacktrace with packaging information for each call in the stack) to a PatternLayout unless another throwable-related pattern is already in the Layout. The result is the pattern for a normal log message.

[%p] %t: %m

Effectively becomes:

[%p] %t: %m<b>%xEx</b>

This means the framework logs not only the error message but also the full stack trace.

[ERROR] main: Unable to open file! java.io.FileNotFoundException: foo.file (No such file or directory)

at java.io.FileInputStream.open(Native Method) ~[?:1.7.0_79]

at java.io.FileInputStream.(FileInputStream.java:146) ~[?:1.7.0_79]

at java.io.FileInputStream.(FileInputStream.java:101) ~[?:1.7.0_79]

at java.io.FileReader.(FileReader.java:58) ~[?:1.7.0_79]

at FooClass.main(FooClass.java:47)

However, printing an exception using %xEx is a relatively expensive operation, possibly resulting in a performance hit, especially if your application frequently logs exceptions. One workaround is to explicitly include %ex in the pattern to request only the stack trace for exceptions.

[%p] %t: %m<b>%ex</b>

Another option is to exclude exception information altogether by appending %xEx{none} (in Log4j).

[%p] %t: %m<b>%xEx{none}</b>

or %nopex (in Logback):

[%p] %t: %m<b>%nopex</b>

Structured Layouts such as JSON and XML can be ideal for logging stack traces, as you'll see in the Parsing Multiline Stack Traces section. These Layouts will automatically break down stack traces into individual fields, making it easy to export them to other programs or a logging service. The same stack trace as above is partially shown below in JSON format:

...

"loggerName" : "FooClass",

"message": "Foo, oh no! ",

"thrown" : {

"commonElementCount" : 0,

"localizedMessage" : "foo.file (No such file or directory)",

"message" : "foo.file (No such file or directory)",

"name" : "java.io.FileNotFoundException",

"extendedStackTrace" : [ {

"class" : "java.io.FileInputStream",

"method" : "open",

"file" : "FileInputStream.java",

...

Typically, exceptions are handled by catching them in a try-catch block. If an exception isn't caught, it could cause the program to terminate. If this happens, capturing any logs can help you troubleshoot the exception to find and fix the root cause. You can, however, set up a default exception handler to automatically log errors if they happen.

The Thread class contains two methods providing the ability to specify an ExceptionHandler for an uncaught exception:

setDefaultUncaughtExceptionHandler handles exceptions occurring on any thread, and setUncaughtExceptionHandler handles exceptions occurring on a specific thread. You can also specify a handler for a ThreadGroup.

The following example sets up an exception handler that logs the exception using java.util.logging. It then starts a thread, which immediately throws a RuntimeException:

// ExceptionDemo.java

import java.util.logging.*;

public class ExceptionDemo {

private static final Logger logger = Logger.getLogger(ExceptionDemo.class.toString());

public static void main(String[] args) {

Thread.setDefaultUncaughtExceptionHandler(new Thread.UncaughtExceptionHandler() {

public void uncaughtException(Thread t, Throwable e) {

logger.log(Level.SEVERE, t + " ExceptionDemo threw an exception: ", e);

};

});

Thread t = new Thread(new adminThread());

t.start();

}

}

// adminThread.java

public class adminThread implements Runnable {

@Override

public void run() {

throw new RuntimeException();

}

}

Here's a sample log showing what an uncaught exception looks like:

May 14, 2019 2:21:15 PM ExceptionDemo$1 uncaughtException

SEVERE: Thread[Thread-1,5,main] ExceptionDemo threw an exception:

java.lang.RuntimeException

at ExceptionDemo$1adminThread.run(ExceptionDemo.java:15)

at java.lang.Thread.run(Thread.java:745)

JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) is a popular format for storing structured data. JSON stores a collection of name/value pairs similar to a HashMap or Hashtable. JSON is portable and versatile, with most modern languages supporting it natively or through readily-available libraries.

JSON supports many basic data types, including strings, numbers, booleans, arrays, and null values. For example, you could represent a computer using the following JSON notation:

{

"manufacturer": "Dell",

"model": "Inspiron",

"hardware": {

"cpu": "Intel Core i7",

"ram": 16384,

"cdrom": null

},

"peripherals": [

{

"type": "monitor",

"manufacturer": "Acer",

"model": "S231HL"

}

]

}

JSON portability makes it ideal for storing log entries. With JSON, a Java log can be read by any number of JSON interpreters. Because the data is already structured, parsing a JSON log can be far easier than parsing a plain text log. The structured data can allow youto filter and analyze your logs using the field values.

There are a number of JSON implementations for Java. One of the most popular is Jackson, which contains a suite of tools for converting objects to and from JSON.

To turn the computer object introduced above into a usable Java object, we'll read it from a file and pass it to a Jackson ObjectMapper, which parses the file into a JsonNode. The JsonNode has the same structure as the original JSON, which allows us to traverse it.

import com.fasterxml.jackson.databind.JsonNode;

import com.fasterxml.jackson.databind.ObjectMapper;

...

ObjectMapper objectMapper = new ObjectMapper();

JsonNode jsonNode = objectMapper.readTree(new FileReader("computer.json"));

System.out.println(jsonNode.get("hardware").get("cpu"));

// Prints "Intel Core i7"

You can also map a JsonNode to a Java class, as well as retrieve the original JSON string using JsonNode.toString():

System.out.println(jsonNode.toString());

// Prints

"{"manufacturer":"Dell","model":"Inspiron","hardware":{"cpu":"Intel Core

i7","ram":16384,"cdrom":null},"peripherals":[{"type":"monitor","manufacturer":"Acer","model":"S231HL"}]}"

However, logging a JsonNode could cause unexpected results when using a structured Layout such as JSONLayout or XMLLayout. Since the JSONObject is treated as a string, it gets embedded into the message field rather than as a separate object. With Log4j, you can embed a JSON string into a JSONLayout by setting the JSONLayout objectMessageAsJsonObject attribute to true.

// log4j2.xml

...

<JsonLayout objectMessageAsJsonObject="true" />

...

Keep in mind many log management systems expect certain fields to contain certain data types. If you store a JSON object in the message field, a log management solution might interpret it as a string instead of a complete JSON object. One way around this is to break up your JSON data into individual string and numeric fields instead of combining them into an object or array.

Logback supports Jackson via the logback-jackson and logback-json-classic libraries, which are part of the logback-contrib project. As with Log4j, you can export logs in JSON format to any Logback Appender.

The Logback Wiki provides a detailed explanation on adding JSON to Logback. While the example in the link uses a Loggly®Appender, the same configuration can work for other Appenders. The following example shows how to write JSON-formatted log entries to a file called myLog.json:

...

<appender name="file" class="ch.qos.Logback.core.FileAppender">

<file>myLog.json</file>

<encoder class="ch.qos.Logback.core.encoder.LayoutWrappingEncoder">

<layout class="ch.qos.Logback.contrib.json.classic.JsonLayout">

<jsonFormatter class="ch.qos.Logback.contrib.jackson.JacksonJsonFormatter"/>

</layout>

</encoder>

</appender>

...

To learn more about Jackson, please see FasterXML on GitHub.

Gson is a popular alternative to the Jackson project, created and maintained by Google. Parsing JSON with Gson is as simple as using two methods: toJson() and fromJson(), which convert Java objects to and from a JSON string, respectively. Gson also works on objects existing in memory, allowing you to map objects you don't have the source code for.

There are several other libraries that work well but are either unmaintained or unsupported. JSON.simple is a simple utility for encoding and decoding Java objects to JSON. JSON-java is a reference implementation by the creator of JSON with additional functionality for converting to other data formats, including web elements.

You can learn more about JSON through the JSON site or by following an interactive, hands-on tutorial through CodeAcademy (note this lesson uses JavaScript, not Java). Online tools such as JSONLint and JSON Editor Online can help with parsing, validating, and formatting JSON code.

With multithreaded applications, especially web services, tracking events can be difficult. When entries are being generated for multiple simultaneous users, how can you tell which actions are associated with which events? What if two users failed to log in or open the same file at the same time? You would need a way to associate each entry with a unique identifier, such as a user ID, session ID, or device ID. This is where ThreadContext comes in handy.

ThreadContext creates log trails by adding unique data stamps to individual log entries. Known as fish tags, these stamps let you distinguish logs using one or more unique values, are managed on a per-thread basis, and last for the lifetime of the thread or until otherwise removed. For instance, if your web application generates a new thread for each user, you can tag log entries created by that thread with that particular user's user ID. This can be useful when you want to trace particular requests, transactions, or users through a complex system.

ThreadContext is built on earlier concepts called the Nested Diagnostic Context (NDC) and Mapped Diagnostic Context (MDC). These concepts were first introduced in Log4j 1 and Logback, then merged into ThreadContext with Log4j 2. However, these acronyms are still used to refer to the underlying techniques, so we'll continue to use them in this guide.

NDC is based on the idea of a stack. Information can be placed (pushed) onto and removed (popped) from the stack. The values in the stack can then be accessed by a Logger without having to pass a value to the logging method explicitly.

The following example uses the NDC and Log4j to associate a username with a log entry. ThreadContext is a static class, so we can access its methods without having to initialize a ThreadContext object.

Here, we store the current values of username (“admin”) and sessionID (“1234”) in the stack using ThreadContext.push(username) and ThreadContext.push(sessionID). ThreadContext.pop() removes individual items from the stack while ThreadContext.removeStack() allows Java to reclaim the memory used by the stack, thereby preventing memory leaks.

import org.apache.logging.Log4j.ThreadContext;

...

String username = "admin";

String password = "1234";

ThreadContext.push(username);

ThreadContext.push(sessionID);

logger.info("Login successful");

ThreadContext.pop();

ThreadContext.remove();

...

The Log4j PatternLayout class extracts values from the NDC through the %x conversion character. If a log event is triggered, the full NDC stack is passed to Log4j.

<PatternLayout pattern="%x %-5p - %m%n" />

Running the program results in the following output:

"admin 1234 INFO - Login successful."

MDC differs from NDC in it stores data as key-value pairs instead of as a stack. This allows you to easily reference individual keys in a Layout. ThreadContext.put(key, value) adds a new key-value pair to the Context, while ThreadContext.remove(key) removes the pair.

To display the same username and session ID in our logs, we'll store both variables as key-value pairs using ThreadContext.put():

import org.apache.logging.Log4j.ThreadContext;

...

ThreadContext.put("username","admin");

ThreadContext.put("sessionID", "1234");

logger.info("Login successful");

ThreadContext.clearMap();

...

Once again, it's important to free the Context once it's no longer in use. ThreadContext.clearMap() removes all values from the MDC. This reduces memory usage and prevents future MDC calls from accessing stale data.

Accessing MDC values in the logging framework is slightly different than with the NDC. Values are accessed using the %X{key} conversion character, where key is any key currently stored in the Context. In this case, we can use %X{username} and %X{sessionID} to retrieve their respective values.

<PatternLayout pattern="%X{username} %X{sessionID} %-5p - %m%n" />

"admin 1234 INFO - Login successful"

If no key is specified, then the contents of the MDC are sent to the Appender using the format {{key, value}, {key, value}}.

MDC access isn't limited to PatternLayouts. When using the JSONFormatter, for instance, all of the values in the MDC are exported.

{

"timestamp":"1431970324945",

"level":"INFO",

"thread":"main",

"mdc":{

"username":"admin",

"sessionID":"1234"

},

"logger":"MyClass",

"message":"Login successful",

"context":"default"

}

Unlike Log4j, Logback doesn't provide a native implementation of NDC. However, the slf4j-ext package provides an NDC implementation using MDC as its base. You can access and manage MDC values natively in Logback using MDC.put(), MDC.remove(), and MDC.clear():

import org.slf4j.MDC;

...

Logger logger = LoggerFactory.getLogger(MDCLogback.class);

...

MDC.put("username", "admin");

MDC.put("sessionID", "1234");

try {

FileReader fr = new FileReader("tmpFile");

}

catch (Exception ex) {

logger.error("Unable to open file.");

}

finally {

MDC.clear();

}

Adding the following pattern to an Appender in Logback.xml results in the same output as Log4j:

<Pattern>[%X{username}] %X{sessionID} %-5p - %m%n</Pattern>

"[admin] 1234 Info - Login successful"

Some frameworks allow you to filter logs based on an attribute. For instance, the Log4j DynamicThresholdFilter automatically adjusts the log level if a key matches a certain value. For instance, if we want to toggle logging messages with the TRACE level, we can create a key called trace-logging-enabled and add a filter to our Log4j configuration.

<Configuration name="MyApp">

<DynamicThresholdFilter key="trace-logging-enabled" onMatch="ACCEPT" onMismatch="NEUTRAL">

<KeyValuePair key="true" value="TRACE" />

</DynamicThresholdFilter>

...

</Configuration>

If the ThreadContext contains a key called trace-logging-enabled, then onMatch and onMismatch determine how to proceed. There are three options available to onMatch and onMismatch:

Below this, we define a KeyValuePair that enables TRACE-level logging when the key is set to true.

Now, the Appenders will log TRACE-level messages when trace-logging-enabled is true, even if the root Logger is set to a higher level.

You might also want to filter certain logs to certain Appenders. In this case, Log4j provides the ThreadContextMapFilter. If we wanted to limit a certain Appender to only log TRACE messages for a certain user, we could add a ThreadContextMapFilter based on the username key.

<Console name="ConsoleAppender" target="SYSTEM_OUT">

<ThreadContextMapFilter onMatch="ACCEPT" onMismatch="DENY">

<KeyValuePair key="username" value="admin" />

</ThreadContextMapFilter>

...

</Console>

For more information, see the Log4j and Logback documentation on DynamicThresholdFilter.

Markers allow you to stamp individual log entries with unique data tokens. Markers can be used to group entries, trigger actions, or filter entries to certain Appenders. You can combine Markers with ThreadContext to improve your ability to search and filter log data.

For example, imagine we have a class that connects to a database. If an exception occurs while opening the database, we'll log the exception as a fatal error. We can create a Marker named DB_ERROR and apply it to the log event.

import org.apache.logging.Log4j.Marker;

import org.apache.logging.Log4j.MarkerManager;

...

final static Marker DB_ERROR = MarkerManager.getMarker("DATABASE_ERROR");

...

logger.fatal(DB_ERROR, "An exception occurred.");

To display the Marker in the log output, add the %marker conversion pattern to your PatternLayout.

<PatternLayout pattern="%p %marker: %m%n" />

[FATAL] DATABASE_ERROR: An exception occurred.

Alternative Layouts such as JSON and XML automatically include Markers in their output.

...

"thread" : "main",

"level" : "FATAL",

"loggerName" : "DBClass",

"marker" : {

"name" : "DATABASE_ERROR"

},

"message" : "An exception occurred.",

...

A benefit of using Markers is they make it easy to search for related logs using centralized logging services.

Marker filters let you specify which Markers will be handled by which Loggers. The marker field is compared against the name of the Marker included in the log event. The Logger will then perform an action if the values match. For example, with Log4j, we can configure an Appender to display only messages using the DB_ERROR Marker by adding the following configuration to an Appender in log4j2.xml:

<MarkerFilter marker="DATABASE_ERROR" onMatch="ACCEPT" onMismatch="DENY" />

If the log entry has a Marker matching the marker field, onMatch determines what to do with the entry. If the Markers don't match, or if the log entry has no Marker, then onMismatch determines what to do with the entry. There are three options available for onMatch and onMismatch:

With Logback, there's a bit more setup. First, add a new EvaluatorFilter to the Appender. Specify the onMatch and onMismatch actions as above. Then, add an OnMarkerEvaluator and pass the name of the Marker to the Evaluator.

<filter class="ch.qos.Logback.core.filter.EvaluatorFilter">

<evaluator class="ch.qos.Logback.classic.boolex.OnMarkerEvaluator">

<marker>DATABASE_ERROR</marker>

</evaluator>

<onMatch>ACCEPT</onMatch>

<onMismatch>DENY</onMismatch>

</filter>

Markers provide a similar function as ThreadContext by stamping log entries with unique data, which can then be accessed by Appenders. Combining them can make your logs easier to index and search, but it helps to know when to use one vs. the others.

NDC, MDC, and ThreadContext are used to associate related log entries. If your application handles multiple simultaneous users, ThreadContext lets you associate a set of log entries with a particular user. Because the ThreadContext is unique for each thread, you can use the same logging methods to automatically group related log entries.

Markers, on the other hand, are commonly used to tag or highlight special events. In the above example, we used the DB_ERROR Marker to tag a SQL-related exception occurring in the method. We could use the DB_ERROR Marker to process the event separately from other events, such as using SMTPAppender to email the DBA.

Tinylog (tinylog) – Lightweight open-source logger

Last updated 2022